In this portfolio, theories have provided both initial direction and retrospective perspective.

While designing and implementing this project we used the theoretical frameworks and guidelines that come with informal learning, environmental education, outdoor education and place based learning.

However, when it comes to communicating and evaluating the process and products, I am attempting to use a different perspective. Considering my background and experience, the best lens I can use to communicate the complexities of this project is that of action research.

Additionally, I have used theoretical frameworks and guidelines from informal learning and practice-based-evidence to evaluate the project.

While designing and implementing this project we used the theoretical frameworks and guidelines that come with informal learning, environmental education, outdoor education and place based learning.

However, when it comes to communicating and evaluating the process and products, I am attempting to use a different perspective. Considering my background and experience, the best lens I can use to communicate the complexities of this project is that of action research.

Additionally, I have used theoretical frameworks and guidelines from informal learning and practice-based-evidence to evaluate the project.

Theoretical Background: Design and Implementation

|

Informal Education:

Informal education, especially in STEM, is “lifelong, life wide, and life-deep” (National Research Council [NRC], 2009). Students spend a majority of their time in non-school settings, and such settings have the potential to facilitate science education. However, if we are going to invest resources into developing informal education the important question is: do students actually learn science in such settings? Luckily, multiple studies have shown that students do learn in informal settings and therefore an investment of resources would be justified (NRC, 2009). Having said that, it is important to note that informal education is not intended to replace formal education, but rather to enhance and complement it (Koran & Shafer, 1982). |

Students on the activity trail

Photo Credit: Sabrina Brown; KBS LTER, MSU |

Out-Door Education:

Students are innately curious about the physical world. In most cases, the experiences they have inside the four walls of a classroom do not satisfy or even take advantage of that curiosity (Smith, 2002). Learning in out-of- school settings therefore allows them to indulge that curiosity and contributes to their cognitive development (Neathery, 1998). In a study assessing the long term impacts of out-of-school experiences Falk & Dierking (1997), most students and adults could recall at least one thing that they had learnt on the field trip. Almost 100% of the adults could remember some actual content that they had learnt on the field trip – and this is several years after the experience.

Students are innately curious about the physical world. In most cases, the experiences they have inside the four walls of a classroom do not satisfy or even take advantage of that curiosity (Smith, 2002). Learning in out-of- school settings therefore allows them to indulge that curiosity and contributes to their cognitive development (Neathery, 1998). In a study assessing the long term impacts of out-of-school experiences Falk & Dierking (1997), most students and adults could recall at least one thing that they had learnt on the field trip. Almost 100% of the adults could remember some actual content that they had learnt on the field trip – and this is several years after the experience.

Environmental Education:

Environmental education stresses the importance of having a citizenry that is not only aware of and connected to the environment they live in, but also has the tools they need to gather and evaluate evidence and use that to make decisions regarding their interactions with their environment (North American Association for Environmental Education [NAAEE], 2019)

Environmental education stresses the importance of having a citizenry that is not only aware of and connected to the environment they live in, but also has the tools they need to gather and evaluate evidence and use that to make decisions regarding their interactions with their environment (North American Association for Environmental Education [NAAEE], 2019)

Place-based Education:

Place-based education leverages local cultural, environmental, economic and political concerns and thus gives an alternative to the same standardised education (Smith, 2007). One of the major strengths of place based education is that it can be contextualised to the needs of the local learners and to their experiences. And since students learn best when they find the material relatable and relevant, using place-based-learning will improve learning outcomes. (Smith, 2002). It is important to note though that place-based learning does not exclude any knowledge and skills that do not directly pertain to that local community, it just includes the ones that do. Making science relevant to their specific circumstances has the potential to encourage more students from under-represented minorities to pursue a career in STEM (Semken & Freeman, 2008).

Place-based education leverages local cultural, environmental, economic and political concerns and thus gives an alternative to the same standardised education (Smith, 2007). One of the major strengths of place based education is that it can be contextualised to the needs of the local learners and to their experiences. And since students learn best when they find the material relatable and relevant, using place-based-learning will improve learning outcomes. (Smith, 2002). It is important to note though that place-based learning does not exclude any knowledge and skills that do not directly pertain to that local community, it just includes the ones that do. Making science relevant to their specific circumstances has the potential to encourage more students from under-represented minorities to pursue a career in STEM (Semken & Freeman, 2008).

Theoretical Background: Perspective

Action Research:

Why Action Research?

In their report on learning science in informal environments, the NRC recommends that the development of tools and materials should be “through iterative processes involving learners, educators, designers, and experts in science, including the sciences of human learning and development.” (NRC, 2009)

Action research is a way of systematically investigating various facets of a problem in order to find a solution that is most effective and relevant to a given situation (Stringer, 2013). It takes for granted that solutions are not one-size-fits-all, and that what works in one scenario might not work in another and seeks to find a customised solution to a highly contextualised problem. Simply put – Action research is a way to figure out how to improve a given situation (E. E. Bell et al., 2008).

While describing community action research, Senge & Scharmer (2008), emphasise that the process is not exclusively focused on finding a solution but gives equal priority to building relationships within the community engaged in the process. In addition to these two themes, action research also empowers the participants to use the knowledge the gain to make the necessary changes in order to better their situation (Masters, 1995).

Why Action Research?

In their report on learning science in informal environments, the NRC recommends that the development of tools and materials should be “through iterative processes involving learners, educators, designers, and experts in science, including the sciences of human learning and development.” (NRC, 2009)

Action research is a way of systematically investigating various facets of a problem in order to find a solution that is most effective and relevant to a given situation (Stringer, 2013). It takes for granted that solutions are not one-size-fits-all, and that what works in one scenario might not work in another and seeks to find a customised solution to a highly contextualised problem. Simply put – Action research is a way to figure out how to improve a given situation (E. E. Bell et al., 2008).

While describing community action research, Senge & Scharmer (2008), emphasise that the process is not exclusively focused on finding a solution but gives equal priority to building relationships within the community engaged in the process. In addition to these two themes, action research also empowers the participants to use the knowledge the gain to make the necessary changes in order to better their situation (Masters, 1995).

|

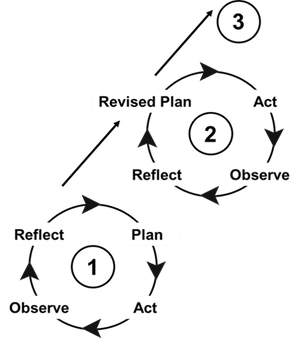

The Action Research Process

Action research in practice can be best thought of as a spiral of repetitive cycles (See figure to the right). Each cycle starts with a planning phase (Plan), followed by the implementation of the plan (Act). The participants keenly observe the process and the results of the action (Observe) and then critically reflect on their observations (Reflect). These reflections then guide the next stage of planning and so on. While from the figure this appears to be a well-demarcated process, in reality it is anything but. Sometimes stages merge with each other, or sometimes in light of new information, abandoning a plan altogether becomes the most ethical decision. For an abbreviated description of the various stages of the process please see: The Action Research Driven Phases of the Project |

The Action Research Spiral.

Taken from (Zuber-Skerrit, 2001) |

Theoretical Background: Evaluation

|

Evaluating The Process: Practice Based Evidence

The term ‘evidence-based practice’ will be most familiar to medical professionals, but is increasingly being used in education. DiCenso, Cullum, & Ciliska (1998), proposed using a combination of research evidence, resources, patients’ preferences and clinical expertise in order to make evidence based decisions about patient care, with some factors having more weight than others. Rycroft‐Malone et al. (2004) proposed that all the four components should be ‘melded-together’ and gave them equal weightage. This movement eventually lead to what we now call practice based evidence (Jaynes, 2014). In education, the term ‘situated generalisation’ has been used to describe similar ideas where teachers generate, validate and use evidence to make decisions to improve their teaching (Simons, Kushner, Jones, & James, 2003). I constructed a Venn diagram based on the one proposed by Rycroft‐Malone et al. (2004), but tailored to our specific situation, which was then used to evaluate the various phases of our project. |

Students on the activity trail

Photo Credit: Jim Wheeler; KBS LTER, MSU |

Evaluating The Products/Outcomes

Attempts to quantitatively measure learning outcomes in informal settings (such as ours) have generated a lot of controversy, including the demand to meet traditional educational measures of achievement in order to qualify for funding (NRC, 2009). It is obvious that these measures have been designed for formal settings and they do not take into consideration the unique affordances or the unique challenges of informal education.

The National Research Council therefore recommends an approach they call the ‘Strands of Science Learning Approach’(NRC, 2009) to organise and assess informal science education. These six strands cover the cognitive, social, emotional and developmental aspects of learning. We evaluated products developed in each phase using these six strands

Evaluating The Partnership

As our trail was evolving, so was our partnership. The partnership kept expanding and not everyone was involved at every point in time. However, I used the CE Teaching & Learning Not-for-Credit Abacus tool developed by Michigan State University’s Outreach and Engagement Office to evaluate the partnership.

Attempts to quantitatively measure learning outcomes in informal settings (such as ours) have generated a lot of controversy, including the demand to meet traditional educational measures of achievement in order to qualify for funding (NRC, 2009). It is obvious that these measures have been designed for formal settings and they do not take into consideration the unique affordances or the unique challenges of informal education.

The National Research Council therefore recommends an approach they call the ‘Strands of Science Learning Approach’(NRC, 2009) to organise and assess informal science education. These six strands cover the cognitive, social, emotional and developmental aspects of learning. We evaluated products developed in each phase using these six strands

Evaluating The Partnership

As our trail was evolving, so was our partnership. The partnership kept expanding and not everyone was involved at every point in time. However, I used the CE Teaching & Learning Not-for-Credit Abacus tool developed by Michigan State University’s Outreach and Engagement Office to evaluate the partnership.

References:

- Bell, E. E., Borda, O. F., Maguire, P., Park, P., Reason, P., & Rowan, J. (2008). PART ONE Groundings. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Action Research (pp. 11–13). SAGE Publications, Ltd.

- DiCenso, A., Cullum, N., & Ciliska, D. (1998). Implementing evidence-based nursing: some misconceptions. Evidence-Based Nursing, 1(2), 38–39.

- Falk, J. H., & Dierking, L. D. (1997). School field trips: Assessing their long‐term impact. Curator: The Museum Journal, 40(3), 211–218.

- Jaynes, S. (2014). Using Principles of Practice-Based Research to Teach Evidence-Based Practice in Social Work. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 11(1–2), 222–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/15433714.2013.850327

- Koran, J. J., & Shafer, L. D. (1982). Learning Science in Informal Settings Outside the Classroom. In M. B. Rowe (Ed.), Education in the 80’s: Science. Washington, DC: National Education Association.

- Masters, J. (1995). The history of action research. In I. Hughes (Ed.), Action Research Electronic Reader. The University of Sydney, online. https://doi.org/http://www.behs.cchs.usyd.edu.au/arow/Reader/rmasters.htm (download)

- National Research Council [NRC]. (2009). Learning Science in Informal Environments: People, Places, and Pursuits. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Neathery, M. F. (1998). Informal learning in experiential settings. Journal of Elementary Science Education, 10(2), 36–49.

- North American Association for Environmental Education [NAAEE]. (2019). K–12 Environmental Education: Guidelines for Excellence. Washington, DC: NAAEE.

- Rycroft‐Malone, J., Seers, K., Titchen, A., Harvey, G., Kitson, A., & McCormack, B. (2004). What counts as evidence in evidence-based practice? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 47(1), 81–90.

- Semken, S., & Freeman, C. B. (2008). Sense of place in the practice and assessment of place-based science teaching. Science Education, 92(6), 1042–1057. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20279

- Senge, P. M., & Scharmer, C. O. (2008). Community action research: Learning as a community of practitioners, consultants and researchers. In P. Reason & H. Bradbury (Eds.), Handbook of Action Research: Concise Paparback Edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Smith, G. A. (2002). Place-based education: Learning to be where we are. Phi Delta Kappan, 83(8), 584–594. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.2001.tb01110.x

- Smith, G. A. (2007). Place-based education: breaking through the constraining regularities of public school. Environmental Education Research, 13(2), 189–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620701285180

- Stringer, E. T. (2013). Action Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Zuber-Skerrit, O. (2001). Action learning and action research: paradigm, praxis and programs. In S. Sankaran, B. Dick, R. Passfield, & P. Swepson (Eds.), Effective Change Management Using Action Research and Action Learning: Concepts, Frameworks, Processes and Applications (pp. 1–20). Lismore, Australia: Southern Cross University Press.